Iowa’s Property Tax Problem

The Problem:

Property taxes are growing faster than what is reasonable.

Iowans are paying an average of 1.5 percent of the value of their home annually in property taxes, which is the 10th-highest property tax burden in the country.

For the better part of the last decade, Governor Reynolds and Republican House and Senate leaders have worked to control state spending to decrease Iowans’ tax burden. Thanks to this leadership, Iowans have welcomed the largest income tax cuts in Iowa history, dropping Iowa to one of the lowest income tax rates in the nation.

Unfortunately, local elected officials have not followed suit. Iowans for Tax Relief believes that property taxes should not exceed one percent of assessed value of a home. As of 2020, Iowans are paying an average of 1.5 percent of the value of their home annually in property taxes. According to the Tax Foundation’s 2023 State Business Tax Climate Index, Iowa makes the cut for the top 10 worst property tax states, coming in at 40th in the nation.

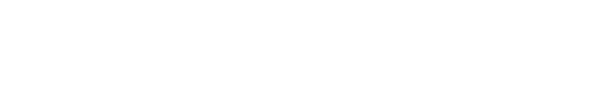

From 2010 to 2020, the population of Iowa rose from 3.05 million to 3.19 million, a 4.7 percent increase. Inflation over this period was a little over 18 percent. In 2010, Iowa cities and counties collected a combined $2.17 billion in property tax receipts. If the size and scope of local government were held constant, adjusted for population growth and inflation, Iowa cities and counties should have collected $2.69 billion in property taxes in 2020, a modest 23.8 percent increase. In reality, cities and counties took in $3.07 billion in property taxes in 2020, a 41.2 percent increase over 2010’s receipts. That’s a tax hike of over 14 percent.

How are these local elected officials getting away with this?

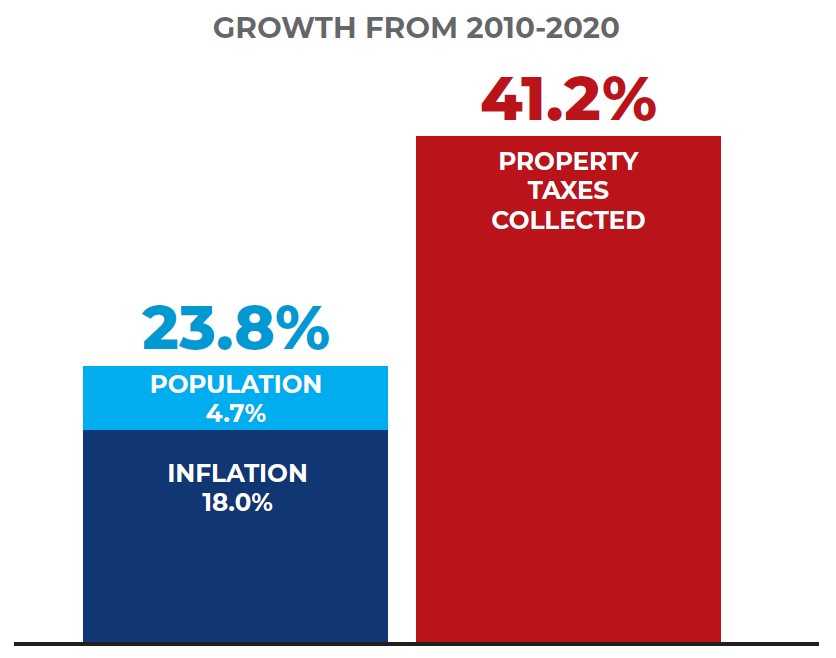

They perpetuate the claim that they did not raise taxes because they didn’t increase, or in some cases even slightly decreased, the levy rate. From 2010 to 2020, the combined assessed value of all properties in Iowa rose 47 percent, increasing from $135.1 billion to $198.6 billion. Considering that the receipts of local governments increased much more in line with assessment growth than with population growth combined with inflation, it seems local elected officials are riding the windfall of new money from assessment increases to grow their size and scope well above what population growth and inflation would dictate is reasonable.

Because local governments are subdivisions of the state, it is time for state lawmakers to act to protect their constituents from local elected officials who are more interested in growing their sprawling government bureaucracies than protecting family budgets.

The Solution:

Step One: A Two-Year Freeze

The first step Iowa lawmakers should consider is an immediate, temporary freeze in property tax bills for existing properties. Assessed property values are expected to rise sharply, and without freezing individuals’ property tax bills, many local governments will leave levy rates unchanged and ride this windfall of new money.

Many local governments are sitting on massive cash reserves—in many cases, cash reserves larger than annual operating budgets. Freezing local government revenue from existing properties does not impact local governments’ ability to increase spending; it merely forces them to draw down cash reserves if revenue from new growth is insufficient to support what local elected officials believe is necessary for operations.

At a time when inflation is soaring well above what has been experienced in decades, families are making tough spending decisions daily to make ends meet. State lawmakers need to force local elected officials to make tough spending decisions as well, instead of increasing the burden on these already-struggling families.

While property taxes are frozen for existing properties, lawmakers should consider long-term options for controlling the growth of property taxes.

Step Two: Enact Longer-Term Options

Stronger Spending Limitations

Lawmakers should look at the many local property tax levies and the limits on those levies. Additionally, lawmakers should consider harder caps on the growth of local budgets. In 2019, the Iowa legislature adopted a two-percent soft cap on the growth of local budgets, but this can easily be exceeded with a super-majority vote of the board or council with an additional public hearing. Further, new growth is not separated from valuation increases on existing properties, so communities experiencing significant growth regularly exceed the two percent of allowable growth without any additional transparency on budget implications for owners of existing properties.

Lawmakers should exercise extreme caution regarding absorbing existing levies into the state general fund. When Iowa lawmakers voted to remove the county mental health levy and fund it at the state level in 2021, 48 of Iowa’s 99 county boards of supervisors did not pass that cost savings on to their property taxpayers. When this happens, it makes income taxes more difficult to cut in the future because it absorbs more general fund dollars while generating little or no savings for property taxpayers—meaning that many Iowans will have to pay more in taxes than they otherwise may have.

“Ratchet-Down” Effect on Local Budgets

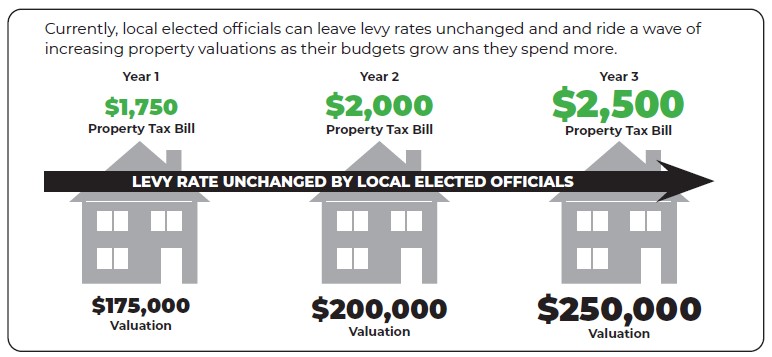

Local elected officials regularly make the claim that they have not raised taxes on local property owners, yet most property owners find that they are paying more in property taxes every year. This is due to the growth of property assessments. When property assessments increase, and local elected officials leave levy rates unchanged, they ride a windfall of new money in the form of tax increases on local property owners.

To close this honesty gap, legislators should consider implementing a “ratchet” on levy rates when property assessments are done. When valuations on existing properties increase, local levy rates should be forced down in direct correlation with property assessment increases among existing properties, generating the same amount of revenue for local governments but holding tax bills the same on average. Local elected officials could choose to raise the levy rate, but they could no longer continue making the claim that they have not raised taxes if they choose to reinstate higher levy rates.

Direct Notification

Any property tax reform should include direct, property-specific notification to property owners regarding potential tax increases. Many people no longer receive a daily, or even weekly, newspaper. Most people do not check their community website with regularity to read public notice postings. People complain most about their taxes when they receive their new property assessments or their property tax bill, but those are not the times when local elected officials are writing their budgets. Many local elected officials claim that they are not contacted during the budgeting process by constituents, and constituents rarely attend public hearings on local budgets, largely because they are confusing, and they may not even be aware they are occurring.

Property owners deserve to be notified of budget hearings with property-specific information about what impact a budget under consideration by a city or county will have on them, as well as the time, date, and location of the public hearing for that budget. Taxpayers need to be empowered with this information so they can hold their local elected officials accountable.

TIF and Abatement Reform

Lawmakers should consider tightening the rules around TIF and abatement utilization. While these economic development tools may have justifiable uses, they also have a great potential for abuse. TIF and abatements increase the property tax burdens on many property owners. The state backfills the school $5.40 levy, but the supplemental levy calculation is done using only the properties without abated property taxes or those outside of TIF districts. This means that the total property value considered is less than the whole, increasing the property tax burden on property owners by reducing the total property value used to calculate the school tax rate per the school funding formula.

Further, because the state is on the hook for the $5.40 levy for school districts, abatements and TIF are absorbing a greater percentage of the general fund every year as the utilization of these tools increases. Particularly egregious is the utilization of never-ending TIF districts, which the state will backfill into perpetuity based on the year these TIF districts were established. These TIF districts must be forced to roll back onto the books at some point, otherwise the increment will increase exponentially with time, along with the state’s burden of backfilling the $5.40 levy. Every time the state general fund is utilized in a manner like this adds one more hurdle in any future attempt at cutting income taxes.

November-Only Bond Issues and Spending Questions

Currently, local jurisdictions have three opportunities to hold bond issue elections in odd-numbered years and two opportunities in even-numbered years. These elections may take place in either March or September, and in odd-numbered year Novembers as well.

In 2017, the Iowa Legislature passed legislation that moved school board elections from September to November to improve voter participation. Most Iowa citizens are aware that elections take place in November each year but don’t have the same awareness about the many other elections that may occur throughout the year.

For this same reason, all bond issue elections should be placed on November election ballots for consideration of the electorate. Iowa code already recognizes the gravity of bond issue decisions by requiring a sixty percent threshold for passage, rather than a simple majority threshold. To ensure that the greatest possible participation of the electorate occurs, bond issue elections should be held at the most recognized time for elections: the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November. Exception may be made for bond issues that may arise in direct response to a natural disaster or other public emergency.

Bond issue questions are some of the most important and impactful decisions on local taxpayers, and maximizing public input by moving all bond issue questions to the November ballot is the right thing to do.